Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Donald Trump and semiconductors: How US tariffs herald an end to the era of hyper-globalisation

The 18th century Scottish economist Adam Smith (1723-90) propounded the “absolute advantage” principle of international trade: Countries should specialise in producing goods that they can make more cheaply than others and import those they cannot manufacture as efficiently.

“The taylor (sic) does not attempt to make his own shoes, but buys them of the shoemaker. The shoemaker does not attempt to make his own clothes, but employs a taylor (sic)… What is prudence in the conduct of every private family, can scarce be folly in that of a great kingdom. If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own industry, employed in a way in which we have some advantage,” Smith wrote in his 1776 classic The Wealth of Nations.

From absolute advantage to comparative advantage

David Ricardo (1772-1823) went one step further with his theory of “comparative advantage”. The London-born stockbroker-turned economist illustrated that with an example of just two countries (England and Portugal) and two goods (cloth and wine) in his 1817 book On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation.

Suppose it took 100 hours to make 1 unit of cloth and 120 hours for 1 unit of wine in England, and the same required only 90 hours and 80 hours respectively in Portugal. Portugal, then, had an ‘absolute advantage’ in producing both goods.

However, Ricardo showed that the two countries could still trade with one another. Sans trade, the Portuguese took 170 hours to make 1 unit each of cloth and wine. The English, likewise, took 220 hours, with the two countries together producing 2 units each of both goods.

But if Portugal specialised in wine, it would make 2.125 units of it in 170 hours. Similarly, by limiting itself to cloth, England would produce 2.2 units in 220 hours. Thus, there would be higher overall output of both wine (from 2 to 2.125) and cloth (2 to 2.2).

Simply put, trade was beneficial even if a country enjoyed an ‘absolute advantage’ in the production of most goods. Portugal gained from producing wine, in which it had a ‘comparative advantage’ of requiring only 80 hours per unit, as against 90 hours for cloth: “It would therefore be advantageous for her to export wine in exchange for cloth.”

Story continues below this ad

Burying Smith and Ricardo: the case of semiconductors

It’s the belief in the Smith-Ricardo theories of specialisation and gains from trade that propelled the era of hyper-globalisation.

That period, from the early 1990s through almost the last decade, conformed to the Ricardian principle “that wine shall be made in France and Portugal, that corn shall be grown in America and Poland, and…hardware and other goods shall be manufactured in England”.

Those theories have now been buried by United States President Donald Trump’s tariffs. The return of the older ‘industrial policy’ had begun even earlier, during the tenure of Trump’s predecessor, Joe Biden.

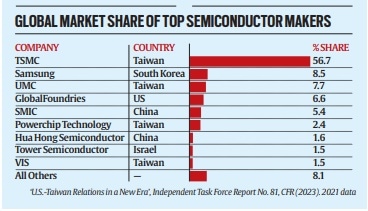

Exemplifying that approach is semiconductors. Taiwanese firms have a more-than-two-thirds share in the global production of these integrated circuits (chips), each containing billions of transistors that control the flow of electric current and providing the computing power for every electronic device from smartphones and laptops to cars and home appliances.

Story continues below this ad

The biggest of these companies, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company Ltd (TSMC), alone had a 56.7% share in 2021 (chart) and 90% in high-end chips used for artificial intelligence (AI) and quantum computing applications.

Until recently, TSMC had 12 semiconductor plants (fabs): nine in Taiwan, two in China, one in the US. The last foundry, at Camas in Washington state, was set up in 1996, and primarily produces chips of 350 nanometer (nm) to 160 nm process nodes (one nm is one-billionth of a metre; the lower the nm value, the more the number of transistors that can be packed into a given area, enabling higher processing power and faster speeds).

Global market share of top semiconductor makers

Global market share of top semiconductor makers

From economic interests to strategic interests

During the high noon of globalisation — when the Smith-Ricardo economic ideas prevailed — it didn’t matter that 60% or more of the world’s semiconductors and 70%-plus of high-performance chips fabricated using sub-7nm nodes were coming from Taiwan.

Taiwan’s dominance in semiconductor fabrication was seen as no different from Indonesia’s and Malaysia’s in palm oil, India’s in IT services or China’s, Bangladesh’s, and Vietnam’s in garment exports.

Story continues below this ad

The system of free trade was founded upon the ideas of comparative advantage (that countries shouldn’t make things they can source from others producing these cheaper at scale) and doux commerce (that economic interdependence makes men less prone to violence or irrational behaviour).

This benign perspective was upended when the US began to get concerned over its own declining share of global semiconductor manufacturing capacity (from 37% in 1990 to 12% in 2020), as well as the strategic implications of Taiwan being home to fabs producing the bulk of the world’s chips.

What if China annexed Taiwan and stationed its military on the island? Conflict in the Taiwan Strait would shut off a key shipping route, halting the production and delivery of chips, triggering a massive supply chain shock.

Such strategic interests-based thinking was boosted by the disruptions from the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Story continues below this ad

In August 2022, Biden signed into law the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) and Science Act. Earlier, in May 2020, TSMC had announced plans to invest $12 billion for a new advanced semiconductor manufacturing facility at Phoenix, Arizona. The firm committed to build a second fab at Phoenix in December 2022 and a third in April 2024, adding up to an investment of “more than $65 billion”.

TSMC’s Arizona plant started production of 4 nm chips in the last quarter of 2024, “with a yield rate comparable to its fabs in Taiwan”.

The company expects to commission its second 3-nm chips fab in 2028, and the third one “using 2 nm or even more advanced process technology” by the decade’s end.

Equally significant is TSMC being provided direct funding of up to $6.6 billion under the CHIPS and Science Act.

Story continues below this ad

Adam Smith balked at restraints on free trade “either by high duties, or by absolute prohibitions”. He asked: “Would it be a reasonable law to prohibit the importation of all foreign wines, merely to encourage the making of claret and burgundy in Scotland?”.

President Trump’s tariffs and the CHIPS law — which aim to bring back manufacturing to the US through subsidies, tax credits and loan guarantees — stand for a different economic principle.

For now, the tide has turned against globalisation, with geopolitics and strategic considerations trumping — quite literally — economics.